Dyslexia's neurobiological origin makes it a learning disability characterized by difficulties in word recognition, decoding, and spelling. Kids with dyslexia exhibit language deficits that affect phonological processing.

Dyslexia affects written and oral language. For example, children with dyslexia struggle with letters, numbers, writing, and phonics. Mapping letters to sounds is at the heart of dyslexia and affects how they decode and encode.

The impact of dyslexia changes over time, which makes early identification essential. Otherwise, they may learn coping mechanisms, such as memorizing words visually and using their often good language skills to verbally explain an answer. However, this will make the diagnosis more complex because they can look like good readers but poor decoders. All readers need a phonetic backup system because even into adulthood, they will have to identify words they don’t know.

Contrary to popular belief, dyslexia doesn't equate to a lack of intelligence. The definition of dyslexia, according to the National Institutes of Health, states that it is a brain-based learning disability that specifically impairs a student's ability to read (Dyslexia | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, 2022). Therefore, it isn't right to associate dyslexia with lower intelligence as these kids tend to have an above average intellect or IQ. Instead, we need to recognize that it is a specific learning disability characterized by poor phonemic awareness and rapid naming skills.

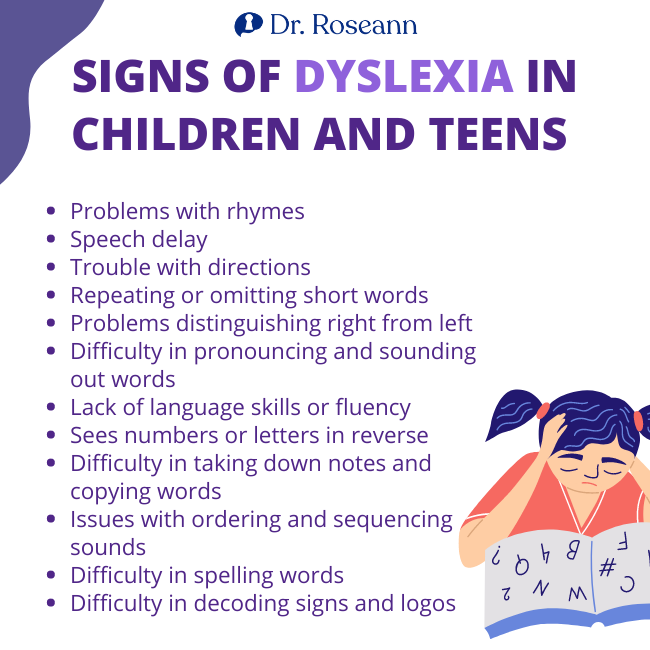

Signs of Dyslexia in Children and Teens

Dyslexia typically shows up even with young children but may be missed depending on their assets and how they compensate.

- Problems with rhymes

- Speech delay

- Trouble with directions

- Repeating or omitting short words

- Problems distinguishing right from left

- Difficulty in pronouncing and sounding out words

- Lack of language skills or fluency

- Sees numbers or letters in reverse

- Difficulty in taking down notes and copying words

- Issues with ordering and sequencing sounds

- Difficulty in spelling words

- Difficulty in decoding signs and logos

Orton-Gillingham Reading Program

Educators Orton and Gillingham developed their method for teaching dyslexic children in 1917, known as the Orton-Gillingham approach for teaching dyslexic children. Their system is also helpful for non-dyslexic students and is still considered the gold standard in dyslexia reading instruction.

The method is specifically designed to teach students to read – from letters and phonics to independent learning with proficient reading skills – but it introduces aspects that can be applied to any subject.

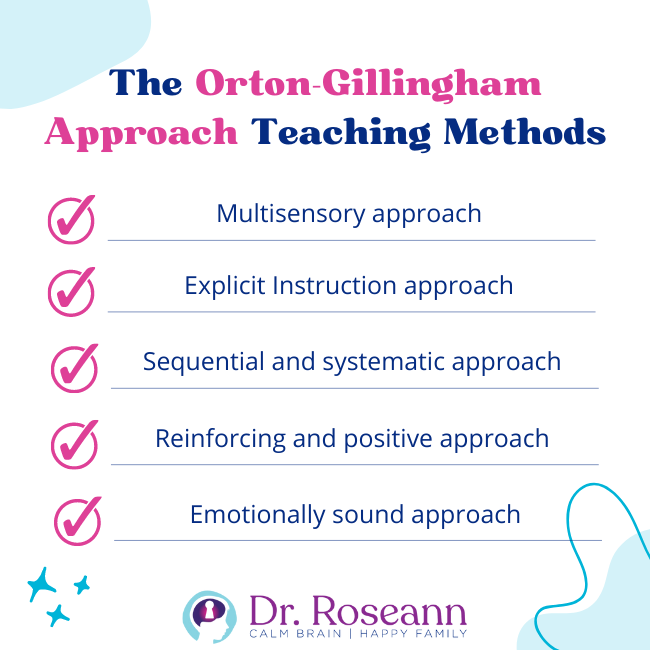

The Orton-Gillingham Approach Teaching Methods

#1 Multisensory approach

The brain processes auditory elements differently in dyslexia. Engaging other senses, such as touch, visual and sound, can work to overcome this deficit. Adding in a kinesthetic approach is the key that unlocks learning in the dyslexic brain. For example, one study shows that multisensory activities using auditory and visual cues improve the writing process of kids with developmental dyslexia, as well as non-dyslexic children (Kast et al., 2007).

#2 Explicit Instruction approach

With a direct instruction approach to teaching, children benefit from knowing what they will learn, why they must understand it, and how it will be taught. Therefore, one of the elements of an effective intervention includes different instructional components that always focus on systematic and explicit instruction in alphabetic code and phonology (Al Otaiba et al., 2009).

OG and Wilson's methods have a clear-cut way that dyslexics to learn how to read. In contrast to most school programs that have “a little of this and that,” these programs have a clear roadmap for remediation.

#3 Sequential and systematic approach

Step-by-step instruction builds upon the skills that the child has already mastered. A systematic approach to teaching organizes and develops instruction functionally. It involves defining well-defined objectives, analyzing the intended audience, evaluating criteria, analyzing and utilizing existing resources, and collaborating with subject matter specialists, instructional system experts, writers, and visual experts (Kelly, 1976).

Wilson, OG, and similar programs have specific steps that must be fully mastered before a child can move to the next instructional level. This is critical. Otherwise, it is like building a house on a shoddy foundation.

#4 Reinforcing and positive approach

Multisensory reading instruction focuses on the child's academic success. Teachers will look at the tasks they have done well and their skills and strengths instead of their overall performance. Implementing positive behavior strategies, such as creating a positive classroom climate, intervening early, and teaching positive behavior, become more effective when combined with engaging academic work.

Incorporating behavior support into instruction, such as pre-teaching, instructional choice, and creating opportunities for response, strengthens the child's proactive behaviors and reduces the likelihood that challenging behavior will occur (DeHartchuck, 2021). Kids with dyslexia need a lot of repetition and reinforcement to learn, and all good multisensory programs do that.

#5 Emotionally sound approach

The Orton-Gillingham method improves students' low self-esteem and supports positive mental attitudes. It does so by focusing on the child's successes to improve their previous skill sets. There are five main dimensions to instruction which are relevant emotions: fear, envy, anger, sympathy, and pleasure.

Fear stems from judging a situation to be threatening, envy stems from a desire to acquire or not acquire something, anger stems from being hindered from reaching a goal, sympathy stems from experiencing other people's need for assistance, and pleasure stems from mastering a situation with devotion (Astleitner, 2000).

Giving children opportunities for success builds the confidence they need to love their dyslexic brains and push through their challenges.

Executive Skills Training

Executive functioning deficits and dyslexia go hand and hand. In a meta-analysis of research relating to executive functioning and dyslexia, findings demonstrated the presence of executive function deficits in children with dyslexia (Lonergan et al., 2019).

Classroom teachers will also best help a child with dyslexia by creating an individualized executive functioning skills training plan targeting the skills and behaviors to help dyslexic kids improve their learning. The outcomes of the training should:

- Increase focus and visual-spatial skills

- Enhance verbal expression

- Boost working memory processing speed

- Improve organization and planning

Here are some of the ways those goals can be achieved:

#1 Shifting and Flexible Thinking

One of the things that teachers can do to help improve shifting and flexible thinking in students with dyslexia is to give them exercises that encourage them to take notes, write summaries, and read for meaning. Teachers should also help them distinguish big ideas from critical details.

#2 Setting Goals

Teachers should help dyslexic students to reach well-defined, doable, and attainable goals. Visuals can be especially helpful in understanding what they are working towards. To do that, teachers should break down the child's goals into smaller, actionable steps and help them identify any obstacles. Teachers should also assist dyslexic learners in overcoming the obstacles they encounter.

#3 Unlocking Working Memory

To unlock the dyslexic child's working memory, teachers may use visual aids so their students can easily remember information. That way, they can easily hold and find information inside their minds. Other methods that interest the child, such as stories and songs, will also help.

#4 Organizing and Prioritizing Ideas and Information

Teachers should show dyslexic students how to divide their tasks into smaller portions, so they don't get overwhelmed and simultaneously help them “see” the end goal. For example, after showing them an end product, high school, middle school, and elementary school students can use outlines and graphs to help them visualize the outcome.

#5 Self-Checking or Self-Monitoring

Teachers should encourage dyslexic students to create checklists and personalized teaching strategies to help them correct their mistakes. For example, using a rubric to check their homework before submission or the five parts to a good paragraph.

Whether you are a teacher or parent looking for ways to support a dyslexic child, early intervention with a multisensory reading program is essential. Reading unlocks all future education, so helping children to become accurate and fluent phonetic readers is just how to do that.

Citations

Al Otaiba, S., McDonald Connor, C., Foorman, B., Schatschneider, C., Greulich, L., & Sidler, J. F. (2009). Identifying and Intervening with Beginning Readers Who Are At-Risk for Dyslexia. Perspectives on Language and Literacy, 35(4), 13–19. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4296731/

Astleitner, H. (2000). Designing Emotionally Sound Instruction: The FEASP-Approach. Instructional Science, 28(3), 169–198. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1003893915778

DeHartchuck, L. (2021, August 3). Positive Behavior Strategies: An Approach for Engaging and Motivating Students. NCLD. https://www.ncld.org/reports-studies/forward-together-2021/positive-behavior-strategies/Dyslexia

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (2022, April 26). Www.ninds.nih.gov. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/dyslexia

Kast, M., Meyer, M., Vögeli, C., Gross, M., & Jäncke, L. (2007). Computer-based multisensory learning in children with developmental dyslexia. Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience, 25(3-4), 355–369. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17943011/

Kelly, R. E. (1976). A Systems Approach to Teaching. In ERIC. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED124184

Lonergan, A., Doyle, C., Cassidy, C., MacSweeney Mahon, S., Roche, R. A. P., Boran, L., & Bramham, J. (2019). A meta-analysis of executive functioning in dyslexia with consideration of the impact of comorbid ADHD. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 31(7), 725–749. https://doi.org/10.1080/20445911.2019.1669609

Always remember… “Calm Brain, Happy Family™”

Are you looking for SOLUTIONS for your struggling child or teen?

Dr. Roseann and her team are all about solutions, so you are in the right place!

There are 3 ways to work with Dr. Roseann:

You can get her books for parents and professionals, including: It’s Gonna Be OK™: Proven Ways to Improve Your Child’s Mental Health, Teletherapy Toolkit™ and Brain Under Attack: A Resource For Parents and Caregivers of Children With PANS, PANDAS, and Autoimmune Encephalopathy.

If you are a business or organization that needs proactive guidance to support employee mental health or an organization looking for a brand representative, check out Dr. Roseann’s media page and professional speaking page to see how we can work together.

Dr. Roseann is a Children’s Mental Health Expert and Therapist who has been featured in/on hundreds of media outlets including, CBS, NBC, FOX News, PIX11 NYC, The New York Times, The Washington Post,, Business Insider, USA Today, CNET, Marth Stewart, and PARENTS. FORBES called her, “A thought leader in children’s mental health.”

She is the founder and director of The Global Institute of Children’s Mental Health and Dr. Roseann Capanna-Hodge. Dr. Roseann is a Board Certified Neurofeedback (BCN) Practitioner, a Board Member of the Northeast Region Biofeedback Society (NRBS), Certified Integrative Medicine Mental Health Provider (CMHIMP) and an Amen Clinic Certified Brain Health Coach. She is also a member of The International Lyme Disease and Associated Disease Society (ILADS), The American Psychological Association (APA), Anxiety and Depression Association of America (ADAA) National Association of School Psychologists (NASP), International OCD Foundation (IOCDF) International Society for Neurofeedback and Research (ISNR) and The Association of Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback (AAPB).

© Roseann-Capanna-Hodge, LLC 2023

Disclaimer: This article is not intended to give health advice and it is recommended to consult with a physician before beginning any new wellness regime. *The effectiveness of diagnosis and treatment vary by patient and condition. Dr. Roseann Capanna-Hodge, LLC does not guarantee certain results.